Tina Havelock Stevens in 2022

Keeper of Time

05.08. - 03.09.2022

Tina Havelock Stevens is an artist who explores the ambiguities of human nature using moving image, photography, sound, improvisational performance, and mixed media. Her works animate an experience of the world that is attuned to emotional responses to the rhythm and movement of structures and environments that we inhabit and traverse. They offer the experience of suspended time, holding our attention to passing moments – mostly encountered. She is known for immersive and transcendent audio-visual installations, often using a drum kit as a spontaneous compositional conduit for historical and personal narratives, environments, and atmospheres.

‘Keeper of Time’ sonically measures the archival. It embraces time travel, the connection to nature and ourselves, touches on the mysteries of DNA and the idea of ‘posthumous collaboration’. The works fuse photography, video installation, text and sound and keep time as the past breathes rhythm into the future.

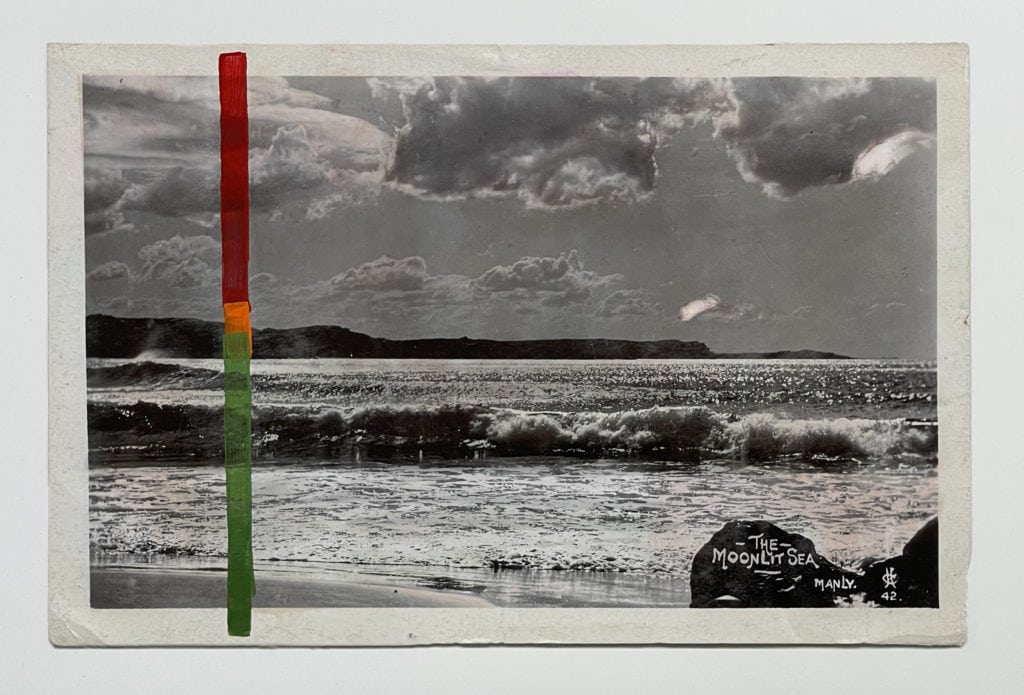

The artist states: “I found a book of postcards when sorting the family home and worked out that they belonged to my Grandfathers mother and grandmother from the first decade of the last century. Inside, I found a carefully arranged album with landscapes from the past and no one left to answer my questions. There’s much beyond the frame. Rather than spontaneously compose and drum the image – something I often do with moving image and/or place, I decided to paint an abstract line which is based on a VU meter. A voluminous meter. The sort of thing you might find on a piece of audio recording equipment. A tool of vision replicating the ears which indicates loudness, energy and intensity – a way to see how something hears perhaps, in this case an emotional gauge.”

Tina will also be re-staging an installation from the inaugural show at Bundanon Museum, as pictured above. The work draws on Malcolm Arnold’s original orchestral music for Robert Helpmann’s Elektra ballet performed at Covent Garden, London, in 1963 through a striking video portrait. The Elektra program’s 1960s design, the bold colours of Arthur Boyd’s set, and the dance reviewer Richard Buckle’s description – “it opens with drums and brass in a burst of boiling rage” – come together to re-construct the drama of the Elektra tragedy. As stated by the Bundanon Trust: “Havelock Stevens’ no stranger to the task of ‘taking up male’ space and re-inhabits the wrath of the Furies in her performance.”

◐ ◑ ◐ ◑

ESSAY BY DANIEL MUDIE CUNNINGHAM: Keeper of Time

The 19th century invention of the postcard speaks to how a newfound photographic literacy was a key ideological tool for comprehending the rapid onset of modernity and its privileging of spectacle and vision. Pictorial representations of tourism and leisure, filtered through an exotic lens, came into reach in a way never before possible. Despite their affordability and mass appeal, a postcard’s ‘othering’ of the world is racialised through its depictions of ‘foreign’ people from faraway places.

While a postcard may be a form of cheap and easy communication, the globetrotting their circulation implies is clearly the domain of the elite, demonstrating the role class plays in constructing the ‘other’. ‘Wishing you were here’: it’s a lovely sentiment from a postcard’s sender, until you consider how the receiver may never get there if their means are limited, grounding their experience and access of the world to the here and now.

Tina Havelock Stevens’ Keeper of Time responds to an album of vintage postcards sourced from her family archive. Postmarked from around 1904 to 1907 during the ‘golden age’ of postcards, they depict scenes from Europe, United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand. All gelatin silver photos, some originally hand-coloured for effect, recto they show idyllic and seemingly unpopulated landscapes, others resplendent with landmarks of the past. Their intimate handheld quality shifts dramatically as the artist scans and scale them up for printing and display in a gallery context, withholding verso inscriptions from view. Imperceptible human figures (colonial settlers among them) suddenly appear as ghostly apparitions on printed card. The collection belonged to the artist’s paternal great great grandmother, Melanie Lovegrove (née de Mestre) and her offspring Sarah Lovegrove (Tina’s great grandmother), of Warren Road, Marrickville in Sydney’s inner west. Plotting through the family tree, things took an interesting turn for the artist. Melanie’s brother Etienne de Mestre had eleven children. The second youngest was none other than Australian musician turned artist, Roy de Maistre.

Working as both musician and artist, Havelock Stevens (who was born exactly a year before de Maistre died) identified an immediate kinship in how he perceived sound through colour. Noted for his landmark chromatic experiments linking the colour spectrum to musical notation, de Maistre’s abstract paintings are visualisations of music, scores for the eye transmitting pictures to the ear. How sound and vision are combined (if not completely synesthetically blurred) is a mainstay for Havelock Stevens and her work. While de Maistre channelled his experiments into pure abstraction, Havelock Stevens applies her emotional temperature tests to these representational postcards. This is another manifestation of how she finds the loaded emotive resonances in place through sound – often through performances where she ‘drums’ loaded sites. The sonic heat from these postcards is referenced by a VU meter. On the surface of each of the repurposed postcards she paints a strip of colour coded frequencies as an indicator of their energy and intensity. Imagine if these pictures could emit sound, is what she images anew.

Some of us are better at archiving our lives than others. It can happen from necessity when a parent or partner dies and with them a lifetime’s imprint on material things is left behind to process and sort. After her mother died in 2019, Havelock Stevens become a custodian of the family archive, a role she embarked upon as the world grinded to a pandemic halt. As access to travel slowed and stopped momentarily, many found comfort in the nostalgia for elsewhere conveyed by keepsakes located in the home. With Keeper of Time, Havelock Stevens turns up the volume on how we look to the archive, often in times of grief and great change, to make sense of human existence and our place as individuals within the collective. What the vacillating VU meter makes loud and clear in this body of work is that the teleological quest for an origin narrative at the heart of our story is never at rest. This is what Jacques Derrida called mal d’archive – archive fever: “It is to burn with a passion. It is never to rest, interminably, from searching for the archive, right where it slips away.” And just as it might slip and waver, the hand of the artist – as painter, as drummer – steadies the beat with renewed rhythm, keeping time through the archive.

Daniel Mudie Cunningham, 2022

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Sign up to be the first for exclusive gallery news, international events, opening information and updates on our artists.